Yeast

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For the use of yeast as a baking ingredient, see baker's yeast.

| Yeast | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Yeast of the species Saccharomyces cerevisiae | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Phyla and Subphyla | |

|

Ascomycota

|

|

By fermentation, the yeast species Saccharomyces cerevisiae converts carbohydrates to carbon dioxide and alcohols – for thousands of years the carbon dioxide has been used in baking and the alcohol in alcoholic beverages.[5] It is also a centrally important model organism in modern cell biology research, and is one of the most thoroughly researched eukaryotic microorganisms. Researchers have used it to gather information about the biology of the eukaryotic cell and ultimately human biology.[6] Other species of yeast, such as Candida albicans, are opportunistic pathogens and can cause infections in humans. Yeasts have recently been used to generate electricity in microbial fuel cells,[7] and produce ethanol for the biofuel industry.

Yeasts do not form a single taxonomic or phylogenetic grouping. The term yeast is often taken as a synonym for Saccharomyces cerevisiae,[8] but the phylogenetic diversity of yeasts is shown by their placement in two separate phyla: the Ascomycota and the Basidiomycota. The budding yeasts ("true yeasts") are classified in the order Saccharomycetales.[9]

Contents |

History

See also: History of wine and History of beer

The word "yeast" comes to us from Old English gist, gyst, and from the Indo-European root yes-, meaning boil, foam, or bubble.[10]

Yeast microbes are probably one of the earliest domesticated organisms.

People have used yeast for fermentation and baking throughout history.

Archaeologists digging in Egyptian ruins found early grinding stones and

baking chambers for yeasted bread, as well as drawings of

4,000-year-old bakeries and breweries.[11] In 1680, the Dutch naturalist Anton van Leeuwenhoek first microscopically observed yeast, but at the time did not consider them to be living organisms but rather globular structures.[12] In 1857, French microbiologist Louis Pasteur proved in the paper "Mémoire sur la fermentation alcoolique" that alcoholic fermentation was conducted by living yeasts and not by a chemical catalyst.[11][13] Pasteur showed that by bubbling oxygen into the yeast broth, cell growth could be increased, but fermentation was inhibited – an observation later called the "Pasteur effect".By the late 18th century, two yeast strains used in brewing had been identified: Saccharomyces cerevisiae, so-called top-fermenting yeast, and S. carlsbergensis, bottom-fermenting yeast. S. cerevisiae has been sold commercially by the Dutch for bread making since 1780; while, around 1800, the Germans started producing S. cerevisiae in the form of cream. In 1825, a method was developed to remove the liquid so the yeast could be prepared as solid blocks.[14] The industrial production of yeast blocks was enhanced by the introduction of the filter press in 1867. In 1872, Baron Max de Springer developed a manufacturing process to create granulated yeast, a technique that was used until the first World War.[15] In the United States, naturally occurring airborne yeasts were used almost exclusively until commercial yeast was marketed at the Centennial Exposition in 1876 in Philadelphia, where Charles L. Fleischmann exhibited the product and a process to use it, as well as serving the resultant baked bread.[16]

Nutrition and growth

Yeasts are chemoorganotrophs, as they use organic compounds as a source of energy and do not require sunlight to grow. Carbon is obtained mostly from hexose sugars, such as glucose and fructose, or disaccharides such as sucrose and maltose. Some species can metabolize pentose sugars like ribose,[17] alcohols, and organic acids. Yeast species either require oxygen for aerobic cellular respiration (obligate aerobes) or are anaerobic, but also have aerobic methods of energy production (facultative anaerobes). Unlike bacteria, there are no known yeast species that grow only anaerobically (obligate anaerobes). Yeasts grow best in a neutral or slightly acidic pH environment.Yeasts vary in what temperature range they grow best. For example, Leucosporidium frigidum grows at -2 to 20 °C (28 to 68 °F), Saccharomyces telluris at 5 to 35 °C (41 to 95 °F), and Candida slooffi at 28 to 45 °C (82 to 113 °F).[18] The cells can survive freezing under certain conditions, with viability decreasing over time.

In general, yeasts are grown in the laboratory on solid growth media or in liquid broths. Common media used for the cultivation of yeasts include potato dextrose agar (PDA) or potato dextrose broth, Wallerstein Laboratories nutrient (WLN) agar, yeast peptone dextrose agar (YPD), and yeast mould agar or broth (YM). Home brewers who cultivate yeast frequently use dried malt extract (DME) and agar as a solid growth medium. The antibiotic cycloheximide is sometimes added to yeast growth media to inhibit the growth of Saccharomyces yeasts and select for wild/indigenous yeast species. This will change the yeast process.

The appearance of a white, thready yeast, commonly known as kahm yeast, is often a byproduct of the lactofermentation (or pickling) of certain vegetables, usually the result of exposure to air. Although harmless, it can give pickled vegetables a bad flavor and must be removed regularly during fermentation.[19]

Ecology

Yeasts are very common in the environment, and are often isolated from sugar-rich material. Examples include naturally occurring yeasts on the skins of fruits and berries (such as grapes, apples or peaches), and exudates from plants (such as plant saps or cacti). Some yeasts are found in association with soil and insects.[20][21] The ecological function and biodiversity of yeasts are relatively unknown compared to those of other microorganisms.[22] Yeasts, including Candida albicans, Rhodotorula rubra, Torulopsis and Trichosporon cutaneum, have been found living in between people's toes as part of their skin flora.[23] Yeasts are also present in the gut flora of mammals and some insects[24] and even deep-sea environments host an array of yeasts.[25][26]An Indian study of seven bee species and 9 plant species found 45 species from 16 genera colonise the nectaries of flowers and honey stomachs of bees. Most were members of the Candida genus; the most common species in honey stomachs was Dekkera intermedia and in flower nectaries, Candida blankii.[27] Yeast colonising nectaries of the stinking hellebore have been found to raise the temperature of the flower, which may aid in attracting pollinators by increasing the evaporation of volatile organic compounds.[22][28] A black yeast has been recorded as a partner in a complex relationship between ants, their mutualistic fungus, a fungal parasite of the fungus and a bacterium that kills the parasite. The yeast have a negative effect on the bacteria that normally produce antibiotics to kill the parasite and so may affect the ants' health by allowing the parasite to spread.[29]

Reproduction

See also: Mating of yeast

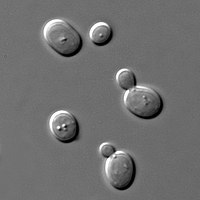

Yeasts, like all fungi, may have asexual and sexual reproductive cycles. The most common mode of vegetative growth in yeast is asexual reproduction by budding.[30] Here, a small bud (also known as a bleb), or daughter cell, is formed on the parent cell. The nucleus

of the parent cell splits into a daughter nucleus and migrates into the

daughter cell. The bud continues to grow until it separates from the

parent cell, forming a new cell.[31] The daughter cell produced during the budding process is generally smaller than the mother cell. Some yeasts, including Schizosaccharomyces pombe, reproduce by fission instead of budding,[30] thereby creating two identically sized daughter cells.In general, under high stress conditions like nutrient starvation, haploid cells will die; under the same conditions, however, diploid cells can undergo sporulation, entering sexual reproduction (meiosis) and producing a variety of haploid spores, which can go on to mate (conjugate), reforming the diploid.[32]

Some pucciniomycete yeasts, in particular species of Sporidiobolus and Sporobolomyces produce aerially dispersed, asexual ballistoconidia.[33]

Uses

The useful physiological properties of yeast have led to their use in the field of biotechnology. Fermentation of sugars by yeast is the oldest and largest application of this technology. Many types of yeasts are used for making many foods: baker's yeast in bread production; brewer's yeast in beer fermentation; yeast in wine fermentation and for xylitol production.[34] So-called red rice yeast is actually a mold, Monascus purpureus. Yeasts include some of the most widely used model organisms for genetics and cell biology.Alcoholic beverages

Alcoholic beverages are defined as beverages that contain ethanol (C2H5OH). This ethanol is almost always produced by fermentation – the metabolism of carbohydrates by certain species of yeast under anaerobic or low-oxygen conditions. Beverages such as mead, wine, beer, or distilled spirits all use yeast at some stage of their production. A distilled beverage is a beverage containing ethanol that has been purified by distillation. Carbohydrate-containing plant material is fermented by yeast, producing a dilute solution of ethanol in the process. Spirits such as whiskey and rum are prepared by distilling these dilute solutions of ethanol. Components other than ethanol are collected in the condensate, including water, esters, and other alcohols, which (in addition to that provided by the oak it is aged in) account for the flavour of the beverage.Beer

Brewing yeasts may be classed as "top cropping" (or "top-fermenting") and "bottom-cropping" (or "bottom-fermenting").[35] Top cropping yeasts are so called because they form a foam at the top of the wort during fermentation. An example of a top-cropping yeast is Saccharomyces cerevisiae, sometimes called an "ale yeast".[36] Bottom-cropping yeasts are typically used to produce lager-type beers, though they can also produce ale-type beers. These yeasts ferment well at low temperatures. An example of bottom-cropping yeast is Saccharomyces pastorianus, formerly known as S. carlsbergensis.Decades ago, taxonomists reclassified S. carlsbergensis (uvarum) as a member of S. cerevisiae, noting that the only distinct difference between the two is metabolic. Lager strains of S. cerevisiae secrete an enzyme called melibiase, allowing it to hydrolyse melibiose, a disaccharide, into more fermentable monosaccharides. Top-cropping and bottom-cropping, cold-fermenting and warm-fermenting distinctions are largely generalizations used by the laypersons to communicate to the general public.[37]

The most common top cropping brewer's yeast, S. cerevisiae, is the same species as the common baking yeast.[38] Brewer's yeast is also very rich in essential minerals and the B vitamins (except B12).[39] However, baking and brewing yeasts typically belong to different strains, cultivated to favour different characteristics: baking yeast strains are more aggressive, to carbonate dough in the shortest amount of time possible; brewing yeast strains act slower, but tend to produce fewer off-flavours and tolerate higher alcohol concentrations (with some strains, up to 22%).

Dekkera/Brettanomyces is a genus of yeast known for their important role in the production of Lambic and specialty sour ales, along with the secondary conditioning of a particular Belgian Trappist beer.[40] The taxonomy of the genus Brettanomyces has been debated since its early discovery and has seen many re-classifications over the years. Early classification was based on a few species that reproduced asexually (anamorph form) through multipolar budding.[41] Shortly after, the formation of ascospores was observed and the genus Dekkera, which reproduces sexually (teleomorph form), was introduced as part of the taxonomy.[42] The current taxonomy includes five species within the genera of Dekkera/Brettanomyces. Those are the anamorphs Brettanomyces bruxellensis, Brettanomyces anomalus, Brettanomyces custersianus, Brettanomyces naardenensis, and Brettanomyces nanus, with teleomorphs existing for the first two species, Dekkera bruxellensis and Dekkera anomala.[43] The distinction between Dekkera and Brettanomyces is arguable with Oelofse et al. (2008) citing Loureiro and Malfeito-Ferreira from 2006 when they affirmed that current molecular DNA detection techniques have uncovered no variance between the anamorph and teleomorph states. Over the past decade, Brettanomyces spp. have seen an increasing use in the craft-brewing sector of the industry with a handful of breweries having produced beers that were primary fermented with pure cultures of Brettanomyces spp. This has occurred out of experimentation as very little information exists regarding pure culture fermentative capabilities and the aromatic compounds produced by various strains. Dekkera/Brettanomyces spp. have been the subjects of numerous studies conducted over the past century, although a majority of the recent research has focused on enhancing the knowledge of the wine industry. Recent research on 8 Brettanomyces strains available in the brewing industry focused on strain specific fermentations and identified the major compounds produced during pure culture anaerobic fermentation in wort.[44]

Wine

Main article: Yeast in winemaking

Yeast is used in winemaking, where it converts the sugars present in grape juice (must) into ethanol. Yeast is normally already present on grape skins. Fermentation can be done with this endogenous "wild yeast,"[45]

but this procedure gives unpredictable results, which depend upon the

exact types of yeast species present. For this reason, a pure yeast

culture is usually added to the must;

this yeast quickly dominates the fermentation. The wild yeasts are

repressed, which ensures a reliable and predictable fermentation.[46]Most added wine yeasts are strains of S. cerevisiae, though not all strains of the species are suitable.[46] Different S. cerevisiae yeast strains have differing physiological and fermentative properties, therefore the actual strain of yeast selected can have a direct impact on the finished wine.[47] Significant research has been undertaken into the development of novel wine yeast strains that produce atypical flavour profiles or increased complexity in wines.[48][49]

The growth of some yeasts, such as Zygosaccharomyces and Brettanomyces, in wine can result in wine faults and subsequent spoilage.[50] Brettanomyces produces an array of metabolites when growing in wine, some of which being volatile phenolic compounds. Together, these compounds are often referred to as "Brettanomyces character", and are often described as "antiseptic" or "barnyard" type aromas. Brettanomyces is a significant contributor to wine faults within the wine industry.[51]

Researchers from University of British Columbia, Canada, have found a new strain of yeast that has reduced amines. The amines in red wine and Chardonnay produce off-flavors and cause headaches and hypertension in some people. About 30 percent of people are sensitive to biogenic amines, such as histamines.[52]

Baking

Main article: Baker's yeast

Yeast, the most common one being S. cerevisiae, is used in baking as a leavening agent, where it converts the fermentable sugars present in dough into the gas carbon dioxide.

This causes the dough to expand or rise as gas forms pockets or

bubbles. When the dough is baked, the yeast dies and the air pockets

"set", giving the baked product a soft and spongy texture. The use of

potatoes, water from potato boiling, eggs,

or sugar in a bread dough accelerates the growth of yeasts. Most yeasts

used in baking are of the same species common in alcoholic

fermentation. In addition, Saccharomyces exiguus (also known as S. minor),

a wild yeast found on plants, fruits, and grains, is occasionally used

for baking. In bread making, the yeast initially respires aerobically,

producing carbon dioxide and water. When the oxygen is depleted, fermentation begins, producing ethanol as a waste product; however, this evaporates during baking.[53]It is not known when yeast was first used to bake bread. The first records that show this use came from Ancient Egypt.[5] Researchers speculate a mixture of flour meal and water was left longer than usual on a warm day and the yeasts that occur in natural contaminants of the flour caused it to ferment before baking. The resulting bread would have been lighter and tastier than the normal flat, hard cake.

Today, there are several retailers of baker's yeast; one of the best-known in North America is Fleischmann's Yeast, which was developed in 1868. During World War II, Fleischmann's developed a granulated active dry yeast, which did not require refrigeration, had a longer shelf life than fresh yeast and that rose twice as fast. Baker's yeast is also sold as a fresh yeast compressed into a square "cake". This form perishes quickly, and must, therefore, be used soon after production. A weak solution of water and sugar can be used to determine whether yeast is expired. In the solution, active yeast will foam and bubble as it ferments the sugar into ethanol and carbon dioxide. Some recipes refer to this as proofing the yeast as it "proves" (tests) the viability of the yeast before the other ingredients are added. When using a sourdough starter, flour and water are added instead of sugar; this is referred to as proofing the sponge.

When yeast is used for making bread, it is mixed with flour, salt, and warm water or milk. The dough is kneaded until it is smooth, and then left to rise, sometimes until it has doubled in size. Some bread doughs are knocked back after one rising and left to rise again. A longer rising time gives a better flavour, but the yeast can fail to raise the bread in the final stages if it is left for too long initially. The dough is then shaped into loaves, left to rise until it is the correct size, and then baked. Bread machine recipes usually call for dried yeast; however, a (wet) sourdough starter can also work.

Bioremediation

Some yeasts can find potential application in the field of bioremediation. One such yeast, Yarrowia lipolytica, is known to degrade palm oil mill effluent,[54] TNT (an explosive material),[55] and other hydrocarbons, such as alkanes, fatty acids, fats and oils.[56] It can also tolerate high concentrations of salt and heavy metals,[57] and is being investigated for its potential as a heavy metal biosorbent.[58]Industrial ethanol production

See also: Bioethanol

The ability of yeast to convert sugar into ethanol has been harnessed by the biotechnology industry to produce ethanol fuel. The process starts by milling a feedstock, such as sugar cane, field corn, or other cereal grains, and then adding dilute sulfuric acid, or fungal alpha amylase enzymes, to break down the starches into complex sugars. A glucoamylase is then added to break the complex sugars down into simple sugars. After this, yeasts are added to convert the simple sugars to ethanol, which is then distilled off to obtain ethanol up to 96% in concentration.[59]Saccharomyces yeasts have been genetically engineered to ferment xylose, one of the major fermentable sugars present in cellulosic biomasses, such as agriculture residues, paper wastes, and wood chips.[60][61] Such a development means ethanol can be efficiently produced from more inexpensive feedstocks, making cellulosic ethanol fuel a more competitively priced alternative to gasoline fuels.[62]

Nonalcoholic beverages

A Kombucha culture fermenting in a jar

Nutritional supplements

See also: Tibicos

Yeast is used in nutritional supplements popular with health conscious individuals and those following vegan diets. It is often referred to as "nutritional yeast" when sold as a dietary supplement. Nutritional yeast is a deactivated yeast, usually S. cerevisiae. It is an excellent source of protein and vitamins,[citation needed] especially the B-complex vitamins, as well as other minerals and cofactors required for growth. It is also naturally low in fat and sodium. Contrary to some claims, it contains little or no vitamin B12.[39] Some brands of nutritional yeast, though not all, are fortified with vitamin B12, which is produced separately by bacteria.Nutritional yeast has a nutty, cheesy flavor that makes it popular as an ingredient in cheese substitutes. It is often used by vegans in place of Parmesan cheese. Another popular use is as a topping for popcorn. It can also be used in mashed and fried potatoes, as well as in scrambled eggs. It comes in the form of flakes, or as a yellow powder similar in texture to cornmeal, and can be found in the bulk aisle of most natural food stores. In Australia, it is sometimes sold as "savory yeast flakes". Though "nutritional yeast" usually refers to commercial products, inadequately fed prisoners have used "home-grown" yeast to prevent vitamin deficiency.[65]

Probiotics

Some probiotic supplements use the yeast S. boulardii to maintain and restore the natural flora in the gastrointestinal tract. S. boulardii has been shown to reduce the symptoms of acute diarrhea in children,[66][67] prevent reinfection of Clostridium difficile,[68] reduce bowel movements in diarrhea-predominant IBS patients,[69] and reduce the incidence of antibiotic,[70] traveler's,[71] and HIV/AIDS[72] associated diarrheas.Aquarium hobby

Yeast is often used by aquarium hobbyists to generate carbon dioxide (CO2) to nourish plants in planted aquariums.[73] A homemade setup is widely used as a cheap and simple alternative to pressurized CO2 systems. While not as effective as these, the homemade setup is considerably cheaper for less-demanding hobbyists.[citation needed]There are several recipes for homemade CO2, but they are variations of the basic recipe: Baker's yeast, with sugar, baking soda, and water, are added to a plastic bottle. A few drops of vegetable oil at the start reduces surface tension and speeds the release of CO2. This will produce CO2 for about 2 or 3 weeks; the use of a bubble counter determines production. The CO2 is injected in the aquarium through a narrow hose and released through a diffuser that helps dissolve the gas in the water. The CO2 is used by plants in the photosynthesis process.

Science

Several yeasts, in particular S. cerevisiae, have been widely used in genetics and cell biology. This is largely because S. cerevisiae is a simple eukaryotic cell, serving as a model for all eukaryotes, including humans for the study of fundamental cellular processes such as the cell cycle, DNA replication, recombination, cell division, and metabolism. Also, yeasts are easily manipulated and cultured in the laboratory, which has allowed for the development of powerful standard techniques, such as yeast two-hybrid, synthetic genetic array analysis, and tetrad analysis. Many proteins important in human biology were first discovered by studying their homologues in yeast; these proteins include cell cycle proteins, signaling proteins, and protein-processing enzymes.On 24 April 1996, S. cerevisiae was announced to be the first eukaryote to have its genome, consisting of 12 million base pairs, fully sequenced as part of the Genome project.[74] At the time, it was the most complex organism to have its full genome sequenced, and took seven years and the involvement of more than 100 laboratories to accomplish.[75] The second yeast species to have its genome sequenced was Schizosaccharomyces pombe, which was completed in 2002.[76][77] It was the sixth eukaryotic genome sequenced and consists of 13.8 million base pairs. As of 2012, over 30 yeast species have had their genomes sequenced and published.[78]

Yeast extract

Main article: Yeast extract

Pathogenic yeasts

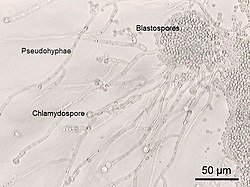

A photomicrograph of Candida albicans showing hyphal outgrowth and other morphological characteristics.

Cryptococcus neoformans is a significant pathogen of immunocompromised people causing the disease termed cryptococcosis. This disease occurs in about 7–9% of AIDS patients in the USA, and a slightly smaller percentage (3–6%) in western Europe.[79] The cells of the yeast are surrounded by a rigid polysaccharide capsule, which helps to prevent them from being recognised and engulfed by white blood cells in the human body.[80]

Yeasts of the Candida genus are another group of opportunistic pathogens that causes oral and vaginal infections in humans, known as candidiasis. Candida is commonly found as a commensal yeast in the mucus membranes of humans and other warm-blooded animals. However, sometimes these same strains can become pathogenic. Here the yeast cells sprout a hyphal outgrowth, which locally penetrates the mucosal membrane, causing irritation and shedding of the tissues.[79] The pathogenic yeasts of candidiasis in probable descending order of virulence for humans are: C. albicans, C. tropicalis, C. stellatoidea, C. glabrata, C. krusei, C. parapsilosis, C. guilliermondii, C. viswanathii, C. lusitaniae, and Rhodotorula mucilaginosa.[81] Candida glabrata is the second most common Candida pathogen after C. albicans, causing infections of the urogenital tract, and of the bloodstream (candidemia).[82]

Food spoilage

Yeasts are able to grow in foods with a low pH, (5.0 or lower) and in the presence of sugars, organic acids and other easily metabolized carbon sources.[83] During their growth, yeasts metabolize some food components and produce metabolic end products. This causes the physical, chemical, and sensible properties of a food to change, and the food is spoiled.[84] The growth of yeast within food products is often seen on their surface, as in cheeses or meats, or by the fermentation of sugars in beverages, such as juices, and semi-liquid products, such as syrups and jams.[83] The yeast of the Zygosaccharomyces genus have had a long history as a spoilage yeast within the food industry. This is due mainly to the fact that these species can grow in the presence of high sucrose, ethanol, acetic acid, sorbic acid, benzoic acid, and sulphur dioxide concentrations,[50] representing some of the commonly used food preservation methods. Methylene blue is used to test for the presence of live yeast cells

酵母菌是一些单细胞真菌,并非系统演化分类的单元。酵母菌是人类文明史中被应用得最早的微生物。可在缺氧环境中生存。目前已知有1000多种酵母,根据酵

母菌产生孢子(子囊孢子和担孢子)的能力,可将酵母分成三类:形成孢子的株系属于子囊菌和担子菌。不形成孢子但主要通过出芽生殖来繁殖的称为不完全真菌,

或者叫“假酵母”(类酵母)。目前已知大部分酵母被分类到子囊菌门。酵母菌在自然界分布广泛,主要生长在偏酸性的潮湿的含糖环境中,而在酿酒中,它也十分

重要。而且猫吃了还会胀大,非常的危险。

编辑本段定义

编辑本段生理

C6H12O6(葡萄糖)→2C2H5OH(酒精)+2CO2+少量能量

在酿酒过程中,乙醇被保留下来;在烤面包或蒸馒头的过程中,二氧化碳将面团发起,而酒精则挥发。

化学元素组分

酵母的化学组成与培养基、培养条件和酵母本身所处的生理状态有关。

一般情况下:

其他元素的含量很少(%)

在酵母中发现的微量元素(mg/kg)

细胞壁

细胞壁厚约25~70nm,细胞壁分为三层,外层为甘露聚糖;中层为蛋白质,其中多数是酶,少数是结构蛋白;内层为葡聚糖,它使细胞保持一定的机械强度。此外,细胞壁还含有少量脂类和几丁质(芽痕)。

不同种属的酵母菌细胞壁不含甘露聚糖。

细胞膜

细胞核

每个细胞通常只有一个核,但也有含有两个核或者甚至多个核。细胞核由核被膜、染色质、核仁和核基质组成。

染色体外DNA

主要有两类,即线粒体DNA和2μm质粒DNA。线粒体DNA是双链DNA,编码大量呼吸酶。

细胞质和细胞器

编辑本段特征

多数酵母可以分离于富含糖类的环境中,比如一些水果(葡萄、苹果、桃等)或者植物分泌物(如仙人掌的汁)。一些酵母在昆虫体内生活。酵母菌是单细胞真核微生物,形态通常有球形、卵圆形、腊肠形、椭圆形、柠檬形或藕节形等,比细菌的单细胞个体要大得多,一般为1~5微米或5~20微米。酵母菌无鞭毛,不能游动。酵母菌具有典型的真核细胞结构,有细胞壁、细胞膜、细胞核、细胞质、液泡、线粒体等,有的还具有微体。

酵母菌的遗传物质组成:细胞核DNA,线粒体DNA,以及特殊的质粒DNA。

未发现其有性阶段的酵母菌称假酵母。

编辑本段用途

在医药工业中,酵母及其制品用于治疗某些消化不良症,并能提高和调整人体的新陈代谢机能。因此,药用酵母的生产在酵母工业中占有重要的地位。

在畜牧业中,酵母广泛用作精饲料以增加饲料中的蛋白质含量,对提高禽畜的出肉率、产蛋率和产乳率,对肉质的改良和毛皮质量的提高均有明显的效果。

编辑本段生殖

简介

有性繁殖方式:子囊孢子。

出芽繁殖

这是酵母菌进行无性繁殖的主要方式。成熟的酵母菌细胞,先长出一个小芽,芽细胞长到一定程度,脱离母细胞继续生长,而后形成新个体。有多边出芽、两端出芽、和三边出芽。

分裂生殖

少数种类的酵母菌与细菌一样,借细胞横分裂而繁殖。

芽裂

母细胞总在一端出芽,并在芽基处形成隔膜,子细胞呈瓶状。这种方式很少。

有性繁殖:在合适的条件下接合子经减数分裂,双倍体核分裂为4~8个单倍体核,形成子囊孢子,包含在由酵母菌细胞壁演变来的子囊中。子囊孢子又可萌发成单倍体营养细胞。

酵母可以通过出芽进行无性生殖,也可以通过形成子囊孢子进行有性生殖。无性生殖即在环境条件适合时,从母细胞上长出一个芽,逐渐长到成熟大小后才与母体分离。

有性生殖

在营养状况不好时,一些可进行有性生殖的酵母会形成孢子(一般来说是四个),在条件适合时再萌发。一些酵母,如假丝酵母(或称念珠菌,Candida)不能进行有性繁殖。

编辑本段生长条件

营养

酸度

酵母菌能在pH值为3.0-7.5 的范围内生长,最适pH 值为pH4.5-5.0。

水分

像细菌一样,酵母菌必须有水才能存活,但酵母需要的水分比细菌少,某些酵母能在水分极少的环境中生长,如蜂蜜和果酱,这表明它们对渗透压有相当高的耐受性。

温度

在低于水的冰点或者高于47℃的温度下, 酵母细胞一般不能生长,最适生长温度一般在20℃~30℃。

氧气

酵母菌在有氧和无氧的环境中都能生长,即酵母菌是兼性厌氧菌,在有氧的情况下,它把糖分解成二氧化碳和水,在有氧存在时,酵母菌生长较快。在缺氧的情况下,酵母菌把糖分解成酒精和二氧化碳。用途 最常提到的酵母酿酒酵母(也称面包酵母)(Saccharomyces cerevisiae),自从几千年前人类就用其发酵面包和酒类,在发酵面包和馒头的过程中面团中会放出二氧化碳。

编辑本段属性

因为酵母多被用于发面,很多人误认为酵母是食品添加剂,

但酵母在全球范围都被认定为食品,它不属于食品添加剂。在中国,酵母属于食品的最直接的法律依据是GB2760-2007,其

规定酵母的食品分类号为16.04;具体可查阅《食品添加剂卫生使用卫生标准》GB2760-2007附录F食品分类系统,即第248页。并且酵母被归为

“其它食品”类,所有酵母产品均应标注有QS证。如果是食品添加剂则必须在产品包装上标注“食品添加剂”字样,无QS标识。

编辑本段产品种类

简介

酵母产品有几种分类方法。以人类食用和作动物饲料的不同目的可分成食用酵母和饲料酵母。食用酵母中又分成面包酵母、益生酵母、药用酵母等;饲料酵母分为酵母益生菌和酵母蛋白饲料等。

面包酵母

又分压榨酵母、活性干酵母和快速活性干酵母。①压榨酵母:采用酿酒酵母生产的含水分70~73%的块状产品。呈淡黄色,具有紧密的结构且易粉碎,有强的发面能力。在4℃可保藏1个月左右,在0℃能保藏2~3个月产品最初是用板框压滤机将离心后的酵母乳压榨脱水得到的,因而被称为压榨酵母,俗称鲜酵母。发面时,其用量为面粉量

的1~2%,发面温度为28~30℃,发面时间随酵母用量、发面温度和面团含糖量等因素而异,一般为1~3小时。②活性干酵母:采用酿酒酵母生产的含水分

8%左右、颗粒状、具有发面能力的干酵母产品。采用具有耐干燥能力、发酵力稳定的醇母经培养得到鲜酵母,再经挤压成型和干燥而制成。发酵效果与压榨酵母相

近。产品用真空或充惰性气体(如

氮气或二氧化碳)的铝箔袋或金属罐包装,货架寿命为半年到1年。与压榨酵母相比,它具有保藏期长,不需低温保藏,运输和使用方便等优点。③快速活性干酵

母:一种新型的具有快速高效发酵力的细小颗粒状(直径小于1mm)产品。水分含量为4~6%。它是在活性干酵母的基础上,采用遗传工程技

术获得高度耐干燥的酿酒酵母菌株,经特殊的营养配比和严格的增殖培养条件以及采用流化床干燥设备干燥而得。与活性干酵母相同,采用真空或充惰气体保藏,货

架寿命为1年以上。与活性干酵母相比,颗粒较小,发酵力高,使用时不需先水化而可直接与面粉混合加水制成面团发酵,在短时间内发酵完毕即可焙烤成食品。

食品酵母

不具有发酵力的繁殖能力,供人类食用的干酵母粉或颗粒状产品。它可通过回收啤酒厂的酵母泥、或为了人类营养的要求专门培养并干燥而得。美国、日本及欧洲一些国家在普通的粮食制品如面包、蛋糕、饼干和烤饼中掺入5%左右的食用酵母粉以提高食品的营养价值。酵母自溶物可作为肉类、果酱、汤类、乳酪、面包类食品、蔬菜及调味料的添加剂;在婴儿食品、健康食品中作为食品营养强化剂。由酵母自溶浸出物制得的5′-核苷酸与味精配合可作为强化食品风味的添加剂。从安琪酵母中提取的浓缩转化酶用作方蛋夹心巧克力的液化剂。从以乳清为原料生产的酵母中提取的乳糖酶,可用于牛奶加工以增加甜度,防止乳清浓缩液中乳糖的结晶,适应不耐乳糖症的消费者的需要。

药用酵母

制造方法和性质与食品酵母相同。由于它含有丰富的蛋白质、维生素和酶等生理活性物质,医药上将其制成酵母片如食母生片,用于治疗因不合理的饮食引起的消化不良症。体质衰弱的人服用后能起到一定程度的调整新陈代谢机能的作用。在酵母培养过程中,如添加一些特殊的元素制成含硒、铬等微量元素的酵母,对一些疾病具有一定的疗效。如含硒酵母用于治疗克山病和大骨节病,并有一定防止细胞衰老的作用;含铬酵母可用于治疗糖尿病等。

饲料酵母

饲料酵母:通常用假丝酵母或脆壁克鲁维酵母经培养、干燥制成,不具有发酵力,细胞呈死亡状态的粉末状或颗粒状产品。它含有丰富的蛋白质(30~40%左右)、B族维生素、氨基酸等物质,广泛用作动物饲料的蛋白质补充物。它能促进动物的生长发育,缩短饲养期,增加肉量和蛋量,改良肉质和提高瘦肉率,改善皮毛的光泽度,并能增强幼禽畜的抗病能力。

编辑本段危害

有些酵母菌对生物或用具是有害的,例如红酵母(Rhodotorula)会生长在浴帘等潮湿的家具上;白色假丝酵母(或称白色念珠菌)(Candida albicans)会生长在阴道衬壁等湿润的人类上皮组织。

编辑本段酵母作用

基因组组成

在酿酒酵母测序计划开始之前,人们通过传统的遗传学方法已确定了酵母中编码RNA或蛋白质的大约2600个基因。通过对酿酒酵母的完整基因组测序,发现在12068kb的全基因组序列中有5885个编码专一性蛋白质的开放阅读框。这意味着在酵母基因组中平均每隔2kb就存在一个编码蛋白质的基因,即整个基因组有72%的核苷酸顺序由开放阅读框组成。这说明酵母基因比其它高等真核生物基因排列紧密。如在线虫基因组中,平均每隔6kb存在一个编码蛋白质的基因;在人类基因组中,平均每隔30kb或更多的碱基才能发现一个编码蛋白质的基因。酵母基因组的紧密性是因为基因间隔区较短与基因中内含子稀少。酵母基因组的开放阅读框平均长度为1450bp即483个密码子,最长的是位于Ⅻ号染色体上

的一个功能未知的开放阅读框(4910个密码子),还有极少数的开放阅读框长度超过1500个密码子。在酵母基因组中,也有编码短蛋白的基因,例如,编码

由40个氨基酸组成的细胞质膜蛋白脂质的PMP1基因。此外,酵母基因组中还包含:约140个编码RNA的基因,排列在Ⅻ号染色体的长末端;40个编码

SnRNA的基因,散布于16条染色体;属于43个家族的275个tRNA基因也广泛分布于基因组中。表1提供了酵母基因在各染色体上分布的大致情况。

染色体简况

染色体编号

长度(bp) 基因数 tRNA基因数

I 23×103 89 4

Ⅱ 807188 410 13

Ⅲ 315×103 182 10

Ⅳ 1531974 796 27

V 569202 271 13

Ⅵ 270×103 129 10

Ⅶ 1090936 572 33

Ⅷ 561×103 269 11

Ⅸ 439886 221 10

X 745442 379 24

Ⅺ 666448 331 16

Ⅻ 1078171 534 22

ⅫI 924430 459 21

ⅪV 784328 419 15

XV 1092283 560 20

XⅥ 948061 487 17

序列测定揭示了酵母基因组中大范围的碱基组成变化。多数酵母染色体由不同程度的、大范围的GC丰富DNA序列和GC

缺乏DNA序列镶嵌组成。这种GC含量的变化与染色体的结构、基因的密度以及重组频率有关。GC含量高的区域一般位于染色体臂的中部,这些区域的基因密度

较高;GC含量低的区域一般靠近端粒和着丝粒,这些区域内基因数目较为贫乏。Simchen等证实,酵母的遗传重组即双链断裂的相对发生率与染色体的GC丰富区相耦合,而且不同染色体的重组频率有所差别,较小的Ⅰ、Ⅲ、Ⅳ和Ⅸ号染色体的重组频率比整个基因组的平均重组频率高。

酵母基因组另一个明显的特征是含有许多DNA重复序列,其中一部分为完全相同的DNA序列,如rDNA与CUP1基因、Ty因子及

其衍生的单一LTR序列等。在基因的间隔区包含大量的三核苷酸重复,引起了人们的高度重视。因为一部分人类遗传疾病是由三核苷酸重复数目的变化所引起的。

还有更多的DNA序列彼此间具有较高的同源性,这些DNA序列被称为遗传丰余(genetic

redundancy)。酵母多条染色体末端具有长度超过几十个kb的高度同源区,它们是遗传丰余的主要区域,这些区域至今仍然在发生着频繁的DNA重组

过程。遗传丰余的另一种形式是单个基因重复,其中以分散类型最为典型,另外还有一种较为少见的类型是成簇分布的基因家族。成簇同源区(cluster

homology

region,简称CHR)是酵母基因组测序揭示的一些位于多条染色体的同源大片段,各片段含有相互对应的多个同源基因,它们的排列顺序与转录方向十分保

守,同时还可能存在小片段的插入或缺失。这些特征表明,成簇同源区是介于染色体大片段重复与完全分化之间的中间产物,因此是研究基因组进化的良好材料,被

称为基因重复的化石。

染色体末端重复、单个基因重复与成簇同源区组成了酵母基因组遗传丰余的大致结构。研究表明,遗传丰余中的一组基因往往具有相同或相似的生理功能,因而它们

中单个或少数几个基因的突变并不能表现出可以辨别的表型,这对酵母基因的功能研究是很不利的。所以许多酵母遗传学家认为,弄清遗传丰余的真正本质和功能意

义,以及发展与此有关的实验方法,是揭示酵母基因组全部基因功能的主要困难和中心问题。

基因组分析

在酵母基因组测序以前,人们已知道在酵母和哺乳动物中有大量基因编码类似的蛋白质。对于一些编码结构蛋白质(如核糖体和细胞骨架中的)在内的同源基因,

人们并不感到意外。但某些同源基因却出乎人们意料,如在酵母中发现的两个同源基因RAS1和RAS2与哺乳动物的H-ras原癌基因高度同源。酵母细胞如

同时缺乏RAS1和RAS2基因,呈现致死表型。在1985年,首次应用RAS1和RAS2基因双重缺陷的酵母菌株进行了功能保守性检测,结果表明,当哺

乳动物的H-ras基因在RAS1和RAS2基因双重缺陷的酵母菌株中表达时,酵母菌株可以恢复生长。因此,酵母的RAS1和RAS2基因不仅与人类的H-ras原癌基因在核苷酸顺序上高度同源,而且在生物学功能方面保守。

随着整个酵母基因组测序计划的完成,人们可以估计有多少酵母基因与哺乳动物基因具有明显的同源性。Botstein

等将所有的酵母基因同GenBank数据库中的哺乳动物基因进行比较(不包括EST顺序),发现有将近31%编码蛋白质的酵母基因或者开放阅读框与哺乳动

物编码蛋白质的基因有高度的同源性。因为数据库中并未能包含所有编码哺乳动物蛋白质的序列,甚至不能包括任何一个蛋白质家族的所有成员,所以上述结果无疑

会被低估。酵母与哺乳动物基因的同源性往往仅限于单个的结构域而非整个蛋白质,这反映了在蛋白质进化过程中功能结构域发生了重排。在酵母5800多个编码

蛋白质的基因中,约41%(~2611个)是通过传统遗传学方法发现的,其余都是通过DNA序列测定所发现。约有20%酵母基因编码的蛋白质与其它生物中

已知功能的基因产物具有不同程度的同源性(其中约6%表现出很强的同源性,约12%表现出稍弱的同源性),从而能初步推测其生物学功能。酵母基因组中有10%基因(约653个)与其它生物中功能未知的蛋白质的基因具有同源性,被称为孤儿基因对或孤儿基因家族(orphan pairs or family);约25%的基因(~1544个)则与所有已发现的蛋白质的基因没有同源性,属首次发现的新基因,是真正意义上的孤儿基因。这些孤儿基因的发现是酵母基因组计划的重要收获,对于其功能的阐明,将大大推进对酵母生命过程的认识,因而引起了众多遗传学家的重视。

为了系统地分析酵母基因组测序发现的3000多个新基因的功能,1996年1月,随着DNA测序工作的结束,欧洲建

立了名为EUROFAN(European Functional Analysis

Network)的研究网络。这一网络由欧洲14个国家的144个实验室组成,它包括服务共同体(service

consortia,A1-A4)、研究共同体(research consortia,B0?B9)和特定功能分析部(specific

functional analysis

nodes,N1-N14)三部分,每个部分下设许多小的分支机构。其中研究共同体中的B0部门负责制作特定的酵母基因缺失突变株。缺失突变株的制作采用

新发展起来的PCR介导的基因置换方法进行,即将来自细菌的卡那霉素抗性基因(KanMX)与线状真菌Ashbya

gossypil的启动子和终止序列构建成表达单元,它可赋予酵母细胞G418以抗性。然后,根据所要置换的染色体DNA序列设计PCR引物,这些引物的

外侧与染色体DNA序列同源,内侧则保证通过PCR可以扩增出KanMX基因,PCR产物直接用于基因置换操作。通过这项技术,可以有目的地将新发现的基

因用KanMX置换,造成基因缺失突变,随后通过系统地研究这些酵母缺失突变株表型有无改变(如生活力、生长速度、接合能力等)以确定这些基因的功能。此

种方法中有两个方面的问题限制实验进程:其一是大部分的突变子(60%~80%)并不显示明显的突变表型,这往往与前面提到的遗传丰余有关;其二是许多突

变子即使发生了表型改变,也不能反映其编码蛋白质的功能,如某些突变子不能在高温或高盐的环境中生长,但这些表型却不能提示任何有关缺失蛋白质在生理功能

方面的信息。

作为模式生物的作用

酵

母作为高等真核生物特别是人类基因组研究的模式生物,其最直接的作用体现在生物信息学领域。当人们发现了一个功能未知的人类新基因时,可以迅速地到任何一

个酵母基因组数据库中检索与之同源的功能已知的酵母基因,并获得其功能方面的相关信息,从而加快对该人类基因的功能研究。研究发现,有许多涉及遗传性疾病

的基因均与酵母基因具有很高的同源性,研究这些基因编码的蛋白质的生理功能以及它们与其它蛋白质之间的相互作用将有助于加深对这些遗传性疾病的了解。此

外,人类许多重要的疾病,如早期糖尿病、小肠癌和心脏疾病,均是多基因遗传性疾病,揭示涉及这些疾病的所有相关基因是一个困难而漫长的过程,酵母基因与人类多基因遗传性疾病相关基因之间的相似性将为我们提高诊断和治疗水平提供重要的帮助。

酵母作为模式生物的最好例子体现在那些通过连锁分析、定位克隆然后测序验证而获得的人类遗传性疾病相关基因的研究

中,后者的核苷酸序列与酵母基因的同源性为其功能研究提供了极好的线索。例如,人类遗传性非息肉性小肠癌相关基因与酵母的MLH1、MSH2基因,运动失

调性毛细血管扩张症相关基因与酵母的TEL1基因,布卢姆氏综合征相关基因与酵母的SGS1基因,都有很高的同源性(见表2)。遗传性非息肉性小肠癌基因

在肿瘤细胞中表现出核苷酸短重复顺序不稳定的细胞表型,而在该人类基因被克隆以前,研究工作者在酵母中分离到具有相同表型的基因突变(msh2和mlh1

突变)。受这个结果启发,人们推测小肠癌基因是MSH2和MLH1的同源基因,而它们在核苷酸序列上的同源性则进一步证实了这一推测。布卢姆氏综合征是一种临床表现为性早熟的遗传性疾病,病人的细胞在体外培养时表现出生命周期缩短的表型,而其相关基因则与酵母中编码蜗牛酶的SGS1基因具有很高的同源性。与来自布卢姆氏综合征个体的培养细胞相似,SGS1基因突变的

酵母细胞表现出显著缩短的生命周期。Francoise等研究了170多个通过功能克隆得到的人类基因,发现它们中有42%与酵母基因具有明显的同源性,

这些人类基因的编码产物大部分与信号转导途径、膜运输或者DNA合成与修复有关,而那些与酵母基因没有明显同源性的人类基因主要编码一些膜受体、血液或免疫系统组分,或人类特殊代谢途径中某些重要的酶和蛋白质。

酿酒酵母基因

人类疾病

人类基因

人类cDNA

GenBank登记号

酵母基因 酵母cDNA

GenBank登记号酵母基因功能

遗传性非息肉性小肠癌MSH2

U03911 MSH2 M84170 DNA修复蛋白

遗传性非息肉性小肠癌MLH1 U07418 MLH1 U07187 DNA修复蛋白

囊性纤维变性CFTR N28668 YCF1 L35237 金属抗性蛋白

威尔逊氏病 WND U11700 CCC2 L36317 铜转运器

甘油激酶缺乏症 GK L13943 GUT1 X69049 甘油激酶

布卢姆氏综合症BLM U39817 SGS1 U22341 蜗牛酶

X-连锁的肾上腺脑白质营养不良 ALD Z21876 PAL1 L38491 过氧化物酶转运器

共济失调性毛细血管扩张症 ATM U26455 TEL1 U31331 P13激酶

肌萎缩性脊髓侧索硬化 SOD1 K00065 SOD1 J03279 过氧化物歧化酶

营养不良性肌萎缩 DM L19268 YPK1 M21307 丝氨酸/苏氨酸蛋白激酶

勒韦氏综合症 OCRL M88162 YIL002C X47047 IPP-5-磷酸酶

I-型神经纤维瘤 NF1 M89914 IRA2 M33779 抑制性的调节蛋白

随着获得高等真核生物更多的遗传信息,人们将会发现有更多的酵母基因与高等真核生物基因具有同源性,因此酵母基因组

在生物信息学领域的作用会显得更加重要,这同时也会反过来促进酵母基因组的研究。与酵母相比,高等真核生物具有更丰富的表型,从而弥补了酵母中某些基因突

变没有明显表型改变的不足。下面将要提到的例子正说明了酵母和人类基因组研究相互促进的关系。人类着色性干皮病是一种常染色体隐性遗传的皮肤疾病,极易发

展成为皮肤癌。早在1970年Cleaver等就曾报道,着色性干皮病和紫外线敏

感的酵母突变体都与缺乏核苷酸切除修复途径(nucleotide excision

repair,NER)有关。1985年,第一个NER途径相关基因被测序并证实是酵母的RAD3基因。1987年,Sung首次报道酵母Rad3p能修

复真核细胞中DNA解旋酶活力的缺陷。1990年,人们克隆了着色性干皮病相关基因xPD,发现它与酵母NER途径的RAD3基因有极高的同源性。随后发

现所有人类NER的基因都能在酵母中找到对应的同源基因。重大突破来源于1993年,发现人类xPBp和xPDp都是转录机制中RNA聚合酶Ⅱ的TFⅡH

复合物的基本组分。于是人们猜测xPBp和xPDp在酵母中的同源基因(RAD3和RAD25)

也应该具有相似的功能,依此线索很快获得了满意的结果并证实了当初的猜测。

酵母作为模式生物的作用不仅是在生物信息学方面的作用,酵母也为高等真核生物提供了一个可以检测的实验系统。例如,可利用异源基因与酵母基因的功能互补以确证基因的功能。据Bassett的不完全统计,到1996年7月15日,至少已发现了71对人类与酵母的互补基因。

六个类型

1、20个基因与生物代谢包括生物大分子的合成、呼吸链能量代谢以及药物代谢等有关

2、16个基因与基因表达调控相关,包括转录、转录后加工、翻译、翻译后加工和蛋白质运输等

3、1个基因是编码膜运输蛋白的

4、7个基因与DNA合成、修复有关

5、7个基因与信号转导有关。

6、17个基因与细胞周期有关。现在,人们发现有越来越多的人类基因可以补偿酵母的突变基因,因而人类与酵母的互补基因的数量已远远超过过去的统计。

在酵母中进行功能互补实验无疑是一种研究人类基因功能的捷径。如果一个功能未知的人类基因可以补偿酵母中某个具有已

知功能的突变基因,则表明两者具有相似的功能。而对于一些功能已知的人类基因,进行功能互补实验也有重要意义。例如与半乳糖血症相关的三个人类基因

GALK2(半乳糖激酶)、GALT(UDP-半乳糖转移酶)和GALE(UDP-半乳糖异构酶)能分别补偿酵母中相应的GAL1、GAL7、GAL10基因突变。在进行互补实验以前,人类和酵母的乳糖代谢途径都已十分清楚,对有关几种酶的活性检测法也十分健全,并已获得其纯品,可以进行一系列生化分

析。随着人类三个半乳糖血症相关基因的克隆分离成功,功能互补实验成为可能,从而在遗传学水平进一步确证了人类半乳糖血症相关基因与酵母基因的保守性。人

们又将这一成果予以推广,利用酵母系统进行半乳糖血症的检测和基因治疗,如区别真正的突变型和遗传多态性,在酵母中模拟多种突变型的组合表型,或筛选基因

内或基因间的抑制突变等。这些方法也同样适用于其它遗传病的研究。

利用异源基因与酵母基因的功能,还能使酵母成为其它生物新基因的筛查工具。通过使用特定的酵母基因突变株,对人类cDNA表达文库进行筛选,从而获得互补的克隆。如Tagendreich等利用酵母的细胞分裂突变型(cdc mutant)分离到多个在人类细胞有丝分裂过程中起作用的同源基因。利用此方法,人们还克隆分离到了农作物、

家畜和家禽等的多个新基因。为了充分发挥酵母作为模式生物的作用,除了发展酵母生物信息学和健全异源基因在酵母中进行功能互补的研究方法外,通过建立酵母

最小的基因组也是一个可行的途径。酵母最小的基因组是指所有明显丰余的基因减少到允许酵母在实验条件下的合成培养基中生长的最小数目。人类cDNA克隆与

酵母中功能已知基因缺陷型进行遗传互补可以确定人类新基因的功能,但是这种互补实验会受到酵母基因组中其它丰余基因的影响。如果构建的酵母最小基因组中所

保留的基因可以被人类或者病毒的DNA序列完全替换,那么替换后的表型将完全取决于外源基因,这将成为一种筛选抗癌和抗病毒药物的分析系统。

在发酵工程中的应用

单细胞真核生物的酵母菌具有比较完备的基因表达调控机制和对表达产物的加工修饰能力。酿酒酵母(Saccharomyces.Cerevisiae)在分子遗传学方面被人们的认识最早,也是最先作为外源基因表达的酵母宿主。1981年酿酒酵母表达了第一个外源基因----干扰素基

因,随后又有一系列外源基因在该系统得到表达干扰素和胰岛素虽然已经利用酿酒酵母大量生产并被广泛应用,当利用酿酒酵母制备时,实验室的结果很令人鼓舞,

但由实验室扩展到工业规模时,其产量迅速下降。原因是培养基中维特质粒高拷贝数的选择压力消失质粒变得不稳定,拷贝数下降。拷贝数是高效表达的必备因素,

因此拷贝数下降,也直接导致外源基因表达量的下降。同时,实验室用培养基成分复杂且昂贵,当采用工业规模能够接受的培养基时,导致了产量的下降。为克服酿

酒酵母的局限,1983年美国Wegner等人最先发展了以甲基营养型酵母(methylotrophic

yeast)为代表的第二代酵母表达系统。甲基营养型酵母包括:Pichia、Candida等.以Pichia.pastoris(毕赤巴斯德酵母)为宿主的外源基因表达系统近年来发展最为迅速,应用也最为广泛。毕赤酵母系统的广泛应用,原因在于该系统除了具有一般酵母所具有的特点外。

编辑本段发展史

早

在公元3000年前,人类开始利用酵母来制作发酵产品。最早在市场上销售的产品是酵母泥,这种产品的特点是发酵速度快,但运输和使用不便,产品的商业化受

到了一定的限制。从销售酵母泥算起,把制造酵母作为一种工业来看,酵母工业的发展已有200余年的历史了。酵母已成为世界上研究最多的微生物之一,是当今生物技术产品研究开发的热点和现代生物技术发展、基因组研究的模式系统。

目前,全球酵母生产能力总计(以干酵母计)超过100万吨,年销售收入超过25亿美元。

20世纪80年代以来,中国酵母工业取得了跨越式发展,拥有了畅销全球的自主创新品牌,酵母产品的研究、生产和应用达到了国际先进水平。

还有以下几个优点:

⑴具有醇氧化酶AOX1基因启动子,这是目前最强,调控机理最严格的启动子之一。

⑵ 表达质粒能在基因组的特定位点以单拷贝或多拷贝的形式稳定整合。

⑶ 菌株易于进行高密度发酵,外源蛋白表达量高。

⑷ 毕赤酵母中存在过氧化物酶体,表达的蛋白贮存其中,可免受蛋白酶的

降解,而且减少对细胞的毒害作用。Pichia.pastoris基因表达系统经过近十年发展,已基本成为较完善的外源基因表达系统,具有易于高密度发

酵,表达基因稳定整合在宿主基因组中,能使产物有效分泌并适当糖基化,培养方便经济等特点。利用强效可调控启动子AOX1,已高效表达了HBsAg、

TNF、EGF、破伤风毒素

C片段、基因工程抗体等多种外源基因,证实该系统为高效、实用、简便,以提高表达量并保持产物生物学活性为突出特征的外源基因表达系统,而且非常适宜扩大

为工业规模。

目前美国FDA已能评价来自该系统的基因工程产品,最近来自该系统的Cephelon制剂已获得FDA批准,所以该

系统被认为是安全的.Pichia.pastoris表达系统在生物工程领域将发挥越来越重要的作用,促进更多外源基因在该系统的高效表达,提供更为广泛

的基因工程产品。

Johns Hopkins大学研究人员成功运用新技术从酵母基因组中找到一些和在酵母细胞分裂时将复制的染色体聚集以保护细胞分裂时酵母遗传完整性相关的基因。

编辑本段保护肝脏

让面粉发酵有很多办法,如小苏打发酵、老面发酵、酵母发酵等。

这些方法原理上都一样,就是通过发酵剂在面团中产生大量二氧化碳气体,蒸煮过程中,二氧化碳受热膨胀,于是面食就变得松软好吃了。

但是前两种方法都各有弊端,小苏打会严重破坏面粉中的B族维生素,老面发酵会使面团产生酸味,只有酵母发酵,不仅让面食味道好,还提高了它的营养价值。

酵母分为鲜酵母、干酵母两种,是一种可食用的、营养丰富的单细胞微生物,营养学上把它叫做“取之不尽的营养源”。除了蛋白质、碳水化合物、脂类以外,酵母还富含多种维生素、矿物质和酶类。有实验证明,每1公斤干酵母所含的蛋白质,相当于5公斤大米、2公斤大豆或2.5公斤猪肉的蛋白质含量。因此,馒头、面包中所含的营养成分比大饼、面条要高出3—4倍,蛋白质增加近2倍。

发酵后的酵母还是一种很强的抗氧化物,可以保护肝脏,有一定的解毒作用。酵母里的硒、铬等矿物质能抗衰老、抗肿瘤、预防动脉硬化,并提高人体的免疫力。发酵后,面粉里一种影响钙、镁、铁等元素吸收的植酸可被分解,从而提高人体对这些营养物质的吸收和利用。

编辑本段作用

使制品疏松

酵母在面团发酵中产生大量的二氧化碳,并由于面筋网络组织的形成,而被留在网状组织内,使烘烤食品组织疏松多孔,体积增大。

酵母还有增加面筋扩展的作用,使发酵时所产生的二氧化碳能保留在面团内,提高面团的持气能力。如用化学数疏松剂则无此作用。

改善风味作用

面团在发酵过程中,经历了一系列复杂的生物化学反应,产生了面包制品特有的发酵香味。同时,便形成了面包制品所特有的芳香,浓郁,诱人食欲的烘烤香味。

增加营养价值

因为酵母的主要成分是蛋白质,几乎占了酵母干物质的一半含量,而且人体必需氨基酸含量充足,尤其是谷物中较缺乏的赖氨酸含量较多。另一方面,含有大量的维生素B1,维生素B2及尼克酸。所以,酵母能提高发酵食品的营养价值。

编辑本段影响因素

简介

在面包的实际生产中,酵母的发酵受到以下因素的影响:

温度

在

一定的温度范围内,随着温度的增加,酵母的发酵速度也增加,产气量也增加,但最高不要超过38℃~39℃。一般正常的温度应控制在26℃~28℃之内,如

果使用快速生产法则不要超过30℃,因为超过该温度,将发酵过速,面团未充分成熟,保气能力则不佳,影响最终产品品质。

PH值

面团的PH值最适于4~6之间。

糖的影响

可以被酵母直接采用的糖是葡萄糖,果糖。蔗糖则需要经过酵母中的转化酶的作用,分解为葡萄糖和果糖后,再为发酵提供能源。还有麦芽糖,是由面粉中的淀粉酶分解面粉内的破碎淀粉而得到的,经酵母中的麦芽糖酶转化变成2分子葡萄糖后也可以被利用。

渗透压的影响

渗透作用就好似指溶剂分子透过半透膜,由溶剂渗入溶液,或由稀溶液渗入浓溶液的现象。

渗透压是指为阻止渗透作用所需要额加给溶液的额外压力,外界介质渗透压的高低,对酵母的活力有较大的影响。是因为酵母细胞的外层的细胞膜是个半透膜,即具有渗透作用,故外界介质的浓度会直接影响酵母的活力,高浓度的糖,盐,无机盐及其他可溶性的固体物质都会造成较高的渗透压力,抑制酵母的发酵。其原因是当外界介质浓度高时,酵母体内的原生物渗出细胞膜,原质浆分离,酵母因此被破坏,而无法生存。在这方面,干酵母比鲜酵母更有较强的适应能力。当然也有一些酵母在高浓度下仍可生存,并发酵。

在面包生产中,影响渗透压大小的主要是糖,盐这

两种原料。当配方中的糖量为0%~5%时,对酵母的发酵不起抑制作用,反而可促进酵母发酵作用。当超过6%时,便会抑制发酵作用,如果超过10%时,发酵

速度会明显减慢,在葡萄糖,果糖,蔗糖和麦芽糖中,麦芽糖的抑制作用比前三种糖小,这是因为麦芽糖的渗透压比其他糖要低。

编辑本段茶酵母

在台湾冻顶山区,人们在制作乌龙茶时,首先会将茶杀青,之后进行低温发酵,发酵之后,酵母菌便功成身退,沉淀在底部。不过这时候的酵母菌早已吸收了乌龙茶的精华养分,将其捞起经过洗净、消毒、干燥等再制造过程,就成了茶酵母。

现在市场上的茶酵母分为三种:1、如上所说加工而成的茶酵母,产量很低,基本没有产量,因为与茶一起分离后收集难度大;2、乌龙茶与发酵液一起干燥后粉碎成粉,基本为乌龙茶,所含酵母很少;3、乌龙茶提取物与啤酒酵母提取物结成,本产品易于收集加工,可规模化生产。

茶酵母用途广泛,时下最流行的适用于减肥瘦身。

茶酵母——含有茶多酚具有高于ve10 倍的抗氧化能力,能够降低血液中性脂肪含量,有效降血脂。还能够改善由肥胖及血脂偏高引起的精神萎靡、困倦的生物碱,让你精神焕发。***啤酒酵母——含有更为丰富的维生素B是茶酵母的3倍相当,酵母铬是茶酵母2倍相当,B族维生素能加速碳水化合物的脂肪的代谢、快速消耗热量使人在瘦身的同时精力充沛;酵母铬降低中性脂肪、协助胰岛素加速糖的代谢。

真茶酵母的概念应该为:含有乌龙茶等减肥的有效成分,并且具有酵母的的特性,现在啤酒酵母也是一种减肥的热销品,说明酵母本身对减肥都是有效的,而茶酵母的优越之处在与其他融具了茶减肥与酵母减肥的特点,更健康,更有效,更安全。

编辑本段啤酒酵母

用于酿造啤酒的酵母。多为酿酒酵母(Sac-charomyces

cerevisiae)的不同品种。E.C.Hansen(1883)开始分离培养酵母并将它用于酿造啤酒。丹麦Carlsberg酿造研究所的下面酵母

是有名的。其它著名的啤酒酵母有德国的Saaz型下面酵母,英、日等国的上面酵母。细胞形态与其它培养酵母相同,为近球形的椭圆体,与野生酵母不同。啤酒

酵母是啤酒生产上常用的典型的上面发酵酵母。除用于酿造啤酒、酒精及其他的饮料酒外,还可发酵面包。菌体维生素、蛋白质含量高,可作食用、药用和饲料酵

母,还可以从其中提取细胞色素C、核酸、谷胱甘肽、凝血质、辅酶A和三磷酸腺苷等。在维生素的微生物测定中,常用啤酒酵母测定生物素、泛酸、硫胺素、吡哆醇和肌醇等。

啤酒酵母在麦芽汁琼脂培养基上菌落为乳白色,有光泽,平坦,边缘整齐。无性繁殖以芽殖为主。能发酵葡萄糖、麦芽糖、半乳糖和蔗糖,不能发酵乳糖和蜜二糖。

按细胞长与宽的比例,可将啤酒酵母分为三组。第一组的细胞多为圆形、卵圆形或卵形(细胞长/宽<2),主要用

于酒精发酵、酿造饮料酒和面包生产。第二组的细胞形状以卵形和长卵形为主,也有圆或短卵形细胞(细胞长/宽≈2)。这类酵母主要用于酿造葡萄酒和果酒,也

可用于啤酒、蒸馏酒和酵母生产。第三组的细胞为长圆形(细胞长/宽>2)。这类酵母比较耐高渗透压和高浓度盐,适合于用甘蔗糖蜜为原料生产酒精。

编辑本段作用原理

鲜味剂对食品风味的作用

在食品中添加鲜味剂,可提高食品总的味觉强度,还可以用来增强食品的一些风味特征,如持续性、温和感、浓厚感等。鲜

味剂的添加量并非越多越好。研究表明MSG在食品重量的0.2%~0.8%时有最好的增味效果,如此相对的5’-IMP约为0.02~0.04%时,可得

当量的增味强度。但还该考虑鲜味剂与NaCl的比例。如将MSG和食盐添

加到鸡汤或加有香辛料的鸡汤中,其最佳比例是0.33%的MSG、0.83%NaCl及0.38%MSG、0.87%NaCl.只有在一特定浓度范围内,

才给予愉快的感受,过多则适得其反。2、掩盖异味、淡盐效应

⑴在0.6%-4.0%NaCL含量范围内,当添加的YE含量在0.4%-3.0%之间时,可增强溶液的咸度口感。⑵当NaCL浓度>7%时,添加

0.4%以上的YE可以不同程度削弱产品的咸度口感,且削弱程度随NaCL浓度和YE加量的上升有增大趋势。YE的性能特点:一.纯天然、富含多种氨基

酸、多肽、呈味核苷酸 其氨基酸成分如下表所示:

测定值mg/100g

|

检验项目

|

测定值mg/lOOg

| |

3028.4

|

1527.5

| ||

1210.1

|

2455.1

| ||

1266.3

|

593.8

| ||

8246.8

|

1142.0

| ||

1591.2

|

2120.5

| ||

1006.5

|

567.0

| ||

47.2

|

1887.7

| ||

1714.6

|

2191.5

| ||

364.0

|

------

| ||

氨基酸总和

|

31415.5

|

二.味道鲜美、香气浓郁、肉质醇厚感强; 三.耐高温,高温条件下可赋予食品更好的风味

编辑本段元素组分

酵母的化学组成与培养基、培养条件和酵母本身所处的生理状态有关。

一般情况下:

其他元素的含量很少(%)

在酵母中发现的微量元素(mg/kg)

铁--90-350 铜:20-135 锌:100-160 钴:15-65

读音:【jiàomǔ】

【解释】: 真菌的一种,黄白色,圆形或卵形,内有细胞核、液泡等。酿酒、制酱、发面等都是利用酵母引起的化学变化。也叫酵母菌或酿母菌。

编辑本段研究进展

测定基因复制上限

日本冈山大学与日本东北大学的研究人员利用独创的方法测定了酵母菌所有基因的复制次数上限,发现大多数基因即使复制100次以上,细胞仍能维持正常功能,而一些基因只复制数次就会引发细胞死亡。

研究小组使用约有6000个基因的酵母菌进行实验,调查它所有基因的复制次数上限,即基因复制次数到何种程度时会导

致细胞死亡。结果发现,有80%以上的基因分别复制超过100次后,酵母菌的细胞依然维持着正常功能。但是,有115个基因只复制数倍就会导致酵母菌死

亡。这些基因多数与细胞内运输和细胞骨架等基础功能有关,还有的基因与制造细胞内蛋白质或蛋白质复合体有关。研究小组认为,这些基因复制数倍后,导致不必

要地大量合成或分解蛋白质,给细胞造成负担,使酵母菌内的平衡严重紊乱,从而导致酵母菌死亡。[1]

No comments:

Post a Comment